Form in Music

Article objectives

Form is the Basic Structure

Every piece of music has an overall plan or structure, the "big picture", so to speak. This is called the form of the music.

It is easy to recognize and grasp the form of some things, because they are small and simple, like a grain of salt, or repetitive, like a wall made of bricks of the same size. Other forms are easy to understand because they are so familiar; if you see dogs more often than you do sea cucumbers, it should be easier for you to recognize the form of an unfamiliar dog than of an unfamiliar sea cucumber. Other things, like a forest ecosystem, or the structure of a government, are so complex that they have to be explored or studied before their structure can be understood.

Musical forms offer a great range of complexity. Most listeners will quickly grasp the form of a short and simple piece, or of one built from many short repetitions. It is also easier to recognize familiar musical forms. The average American, for example, can distinguish easily between the verses and refrain of any pop song, but will have trouble recognizing what is going on in a piece of music for Balinese gamelan. Classical music traditions around the world tend to encourage longer, more complex forms which may be difficult to recognize without the familiarity that comes from study or repeated hearings.

You can enjoy music without recognizing its form, of course. But understanding the form of a piece helps a musician put together a more credible performance of it. Anyone interested in music theory or history, or in arranging or composing music, must have a firm understanding of form. And being able to "see the big picture" does help the listener enjoy the music even more.

Describing Form

Musicians traditionally have two ways to describe the form of a piece of music. One way involves labelling each large section with a letter. The other way is to simply give a name to a form that is very common.

Labeling Form With Letters

Letters can be used to label the form of any piece of music, from the simplest to the most complex. Each major section of the music is labelled with a letter; for example, the first section is the A section. If the second section (or third or fourth) is exactly the same as the first, it is also labelled A. If it is very much like the A section, but with some important differences, it can be labelled A' (pronounced "A prime"). The A' section can also show up later in the piece, or yet another variation of A, A'' (pronounced "A double prime") can show up, and so on.

The first major section of the piece that is very different from A is labelled B, and other sections that are like it can be labelled B, B', B'', and so on. Sections that are not like A or B are labelled C, and so on.

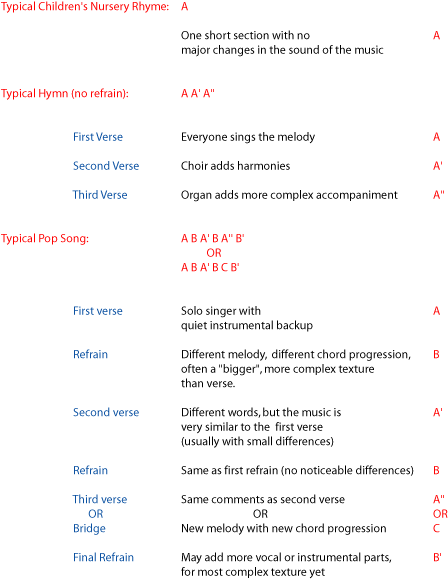

How do you recognize the sections? With familiar kinds of music, this is pretty easy. (See Figure 1 for some examples of forms that will be familiar to most listeners.) With unfamiliar types of music, it can be more of a challenge. Whether the music is classical, modern, jazz, or pop, listen for repeated sections of music. Also, listen for big changes, in the rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, and timbre. A new section that is not a repetition will usually have noticeable differences in more than one of these areas.

Figure 1: Most folk and popular music features simple forms that encourage participation.

When listening to songs, listen for:

\(\bullet\) Verses have the same melody but different words.

\(\bullet\) Refrains have the same melody and the same words.

\(\bullet\) Bridge Sections are new material that appears late in the song, usually appearing only once or twice, often in place of a verse and usually leading into the refrain.

\(\bullet\) Instrumentals are important sections that have no vocals. They can come at the beginning or end, or in between other sections. Is there more than one? Do they have the same melody as a verse or refrain? Are they similar to each other?

While discussing a piece of music in detail, musicians may also use letters to label smaller parts of the piece within larger sections, even down to labelling individual phrases. For example, the song "The Girl I Left Behind" has many verses with no refrain, an A A' A''- type form. However, a look at the tune of one verse shows that within that overall form is an A A' B A'' phrase structure.

Figure 2: In detailed discussions of a piece of music, smaller sections, and even individual phrases, may also be labelled with letters, in order to discuss the piece in greater detail. The A A B A form of this verse is very common, found in verses of everything from folk to jazz to pop music. Verses of blues songs are more likely to have an A A' B form.

Naming Forms

Often a musical form becomes so popular with composers that it is given a name. For example, if a piece of music is called a "theme and variations", it is expected to have an overall plan quite different from a piece called a "rondo". (Specifically, the theme and variations would follow an A A' A'' A'''... plan, with each section being a new variation on the theme in the first section. A rondo follows an A B A C A ... plan, with a familiar section returning in between sections of new music.)

Also, many genres of music tend to follow a preset form, like the "typical pop song form" in Figure 1. A symphony, for example, is usually a piece of music written for a fairly large number of instruments. It is also associated with a particular form, so knowing that a piece of music is called a symphony should lead you to expect certain things about it. For example, listeners familiar with the symphonic form expect a piece called a symphony to have three or four (depending on when it was written) main sections, called movements. They expect a moment of silence in between movements, and also expect the movements to sound very different from each other; for example if the first movement is fast and loud, they might expect that the second movement would be slow and quiet. If they have heard many symphonies, they also would not be at all surprised if the first movement is in sonata form and the third movement is based on a dance.

NOTE: Although a large group of people who play classical music together is often called a symphony, the more accurate term for the group is orchestra. The confusion occurs because many orchestras call themselves "symphony orchestras" because they spend so much time playing symphonies (as opposed to, for example, an "opera orchestra" or a "pops orchestra").

Other kinds of music are also so likely to follow a particular overall plan that they have become associated with a particular form. You can hear musicians talk about something being concerto form or sonata form, for example (even if the piece is not technically a concerto or sonata). Particular dances (a minuet, for example), besides having a set tempo and time signature, will sometimes have a set form that suits the dance steps. And many marches are similar enough in form that there are names for the expected sections (first strain, second strain, trio, break strain).

But it is important to remember that forms are not sets of rules that composers are required to follow. Some symphonies don't have silence between movements, and some don't use the sonata form in any of their movements. Plenty of marches have been written that don't have a trio section, and the development section of a sonata movement can take unexpected turns. And hybrid forms, like the sonata rondo, can become popular with some composers. After all, in architecture, "house" form suggests to most Americans a front and back door, a dining room off the kitchen, and bedrooms with closets, but an architect is free to leave out the dining room, and put the main door at the side of the house and the closets in the bathrooms. Whether a piece of music is a march, a sonata, or a theme and variations, the composer is always free to experiment with the overall architecture of the piece.

Being able to spot that overall architecture as we listen - knowing, so to speak, which room we are in right now - gives us important clues that help us understand and appreciate the music.

Some Common Forms

\(\bullet\) Through-composed - One section (usually not very long) that does not contain any large repetitions. If a short piece includes repeated phrases, it may be classified by the structure of its phrases.

\(\bullet\) Strophic - Composed of verses. The music is repeated sections with fairly small changes. May or may not include a refrain.

\(\bullet\) Variations - One section repeated many times. Most commonly, the melody remains recognizable in each section, and the underlying harmonic structure remains basically the same, but big changes in rhythm, tempo, texture, or timbre keep each section sounding fresh and interesting. Writing a set of variations is considered an excellent exercise for students interested in composing, arranging, and orchestration.

\(\bullet\) Jazz standard song form - Jazz utilizes many different forms, but one very common form is closely related to the strophic and variation forms. A chord progression in A A B A form (with the B section called the bridge) is repeated many times. On the first and last repetition, the melody is played or sung, and soloists improvise during the other repetitions. The overall form of verse-like repetition, with the melody played only the first and final times, and improvisations on the other repetitions, is very common in jazz even when the A A B A song form is not being used.

\(\bullet\) Rondo - One section returns repeatedly, with a section of new music before each return. (A B A C A ; sometimes A B A C A B A)

\(\bullet\) Dance forms - Dance forms usually consist of repeated sections (so there is plenty of music to dance to), with each section containing a set number of measures (often four, eight, sixteen, or thirty-two) that fits the dance steps. Some very structured dance forms (Minuet, for example) are associated even with particular phrase structures and harmonic progressions within each section.

\(\bullet\) Binary Form - Two different main sections (A B). Commonly in Western classical music, the A section will move away from the tonic, with a strong cadence in another key, and the B section will move back and end strongly in the tonic.

\(\bullet\) Ternary Form - Three main sections, usually A B A or A B A'.

\(\bullet\) Cyclic Form - There are two very different uses of this term. One refers to long multimovement works (a "song cycle", for example) that have an overarching theme and structure binding them together. It may also refer to a single movement or piece of music with a form based on the constant repetition of a single short section. This may be an exact repetition (ostinato) in one part of the music (for example, the bass line, or the rhythm section), while development, variation, or new melodies occur in other parts. Or it may be a repetition that gradually changes and evolves. This intense-repetition type of cyclic form is very common in folk musics around the world and often finds its way into classical and popular musics, too.

\(\bullet\) Sonata form - may also be called sonata-allegro or first-movement form. It is in fact often found in the first movement of a sonata, but it has been an extremely popular form with many well-known composers, and so can be found anywhere from the first movement of a quartet to the final movement of a symphony. In this relatively complex form (too complex to outline here), repetition and development of melodic themes within a framework of expected key changes allow the composer to create a long movement that is unified enough that it makes sense to the listener, but varied enough that it does not get boring.